Today we’re looking at the interwoven relationships between stadium-size and attendance and a team’s performance at home and away. We’ll look at how this relationship changed in 2020 when fans were not able to attend most games.

We’re going to try to separate the attendance from the venue size to see if having a packed house makes a difference, regardless of a team’s overall strength.

First, a few primers to understand the data we’re dealing with.

Let’s look at the distribution of venue sizes in college football.

The most popular stadium size appears to be right around 30,000 seats. I’m not sure if this is a rounding thing, or if it just a nice number that a lot of teams settled on. Either way, there are a handful of college football cathedrals, with 90,000+ capacity, but most are under 60,000.

And, believe it or not, the size of your stadium matters. There is indeed a relationship between stadium size and the performance of your team at home, although this can almost certainly be chalked up to the best, most-historic teams in college football growing their stadium size over time to accommodate the demands of their fans. And whether that drives good recruits and good results, or vice-versa, the best teams typically play in the largest stadiums (in the past 20 years).

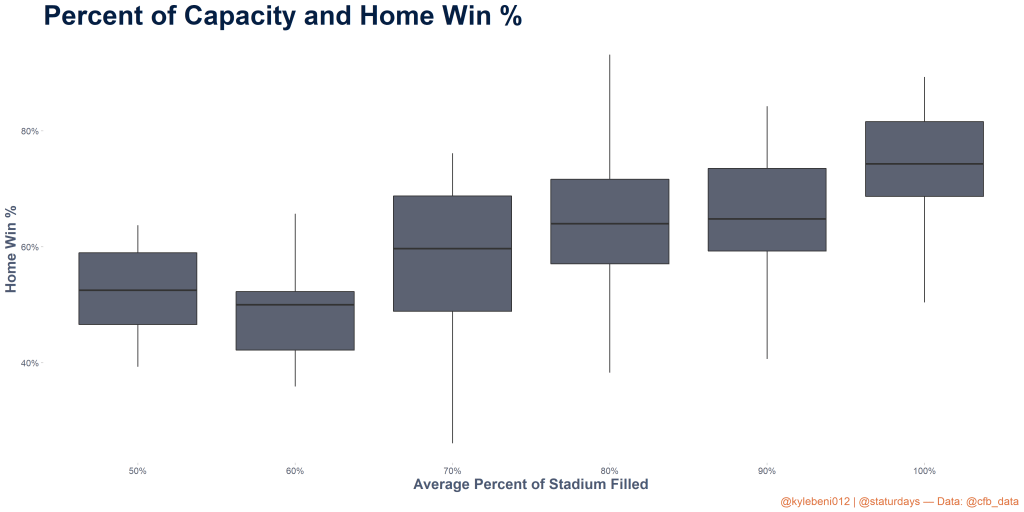

As you can see, there is a slight positive relationship, and as stadium capacity increases, the uncertainty of results is narrower and teams tend to have a winning season at home. However, actual attendance at these games appears to be a more important factor.

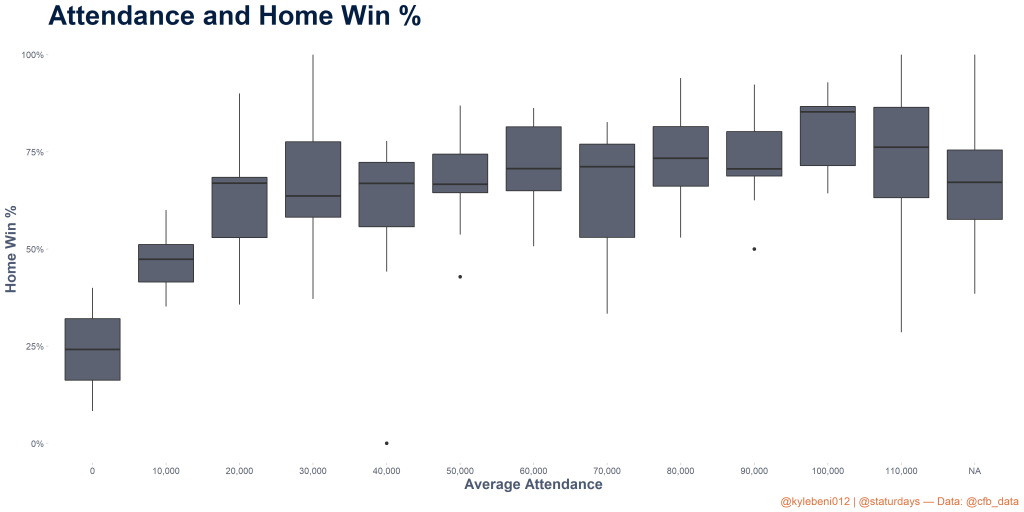

Now we have to take this with a grain of salt, because attendance data can be murky. Some games have no attendance data at all. Others may be way off. It’s impossible to be certain, but there’s at least some positive trend between fans showing up to your games and playing well at home. This shouldn’t come as much of a surprise, although it is surprising that the difference between 50,000 fans and 100,000 seems negligible, indicating that the home field advantage of some of the largest brands in college football might not be all it’s cracked up to be. Of course, the biggest teams are also probably playing some pretty tough opponents in those mega stadiums.

When we put all of these relationships—stadium capacity, raw attendance, and percent of the stadium filled—side by side, we see that they all have a pretty similar relationship to one another and a pretty similar relationship to wins.

Empty Stadiums

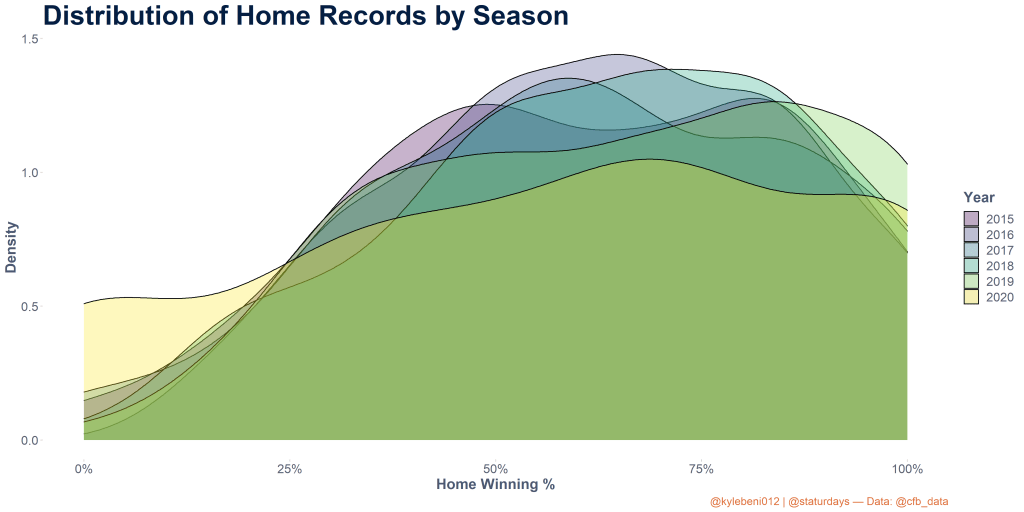

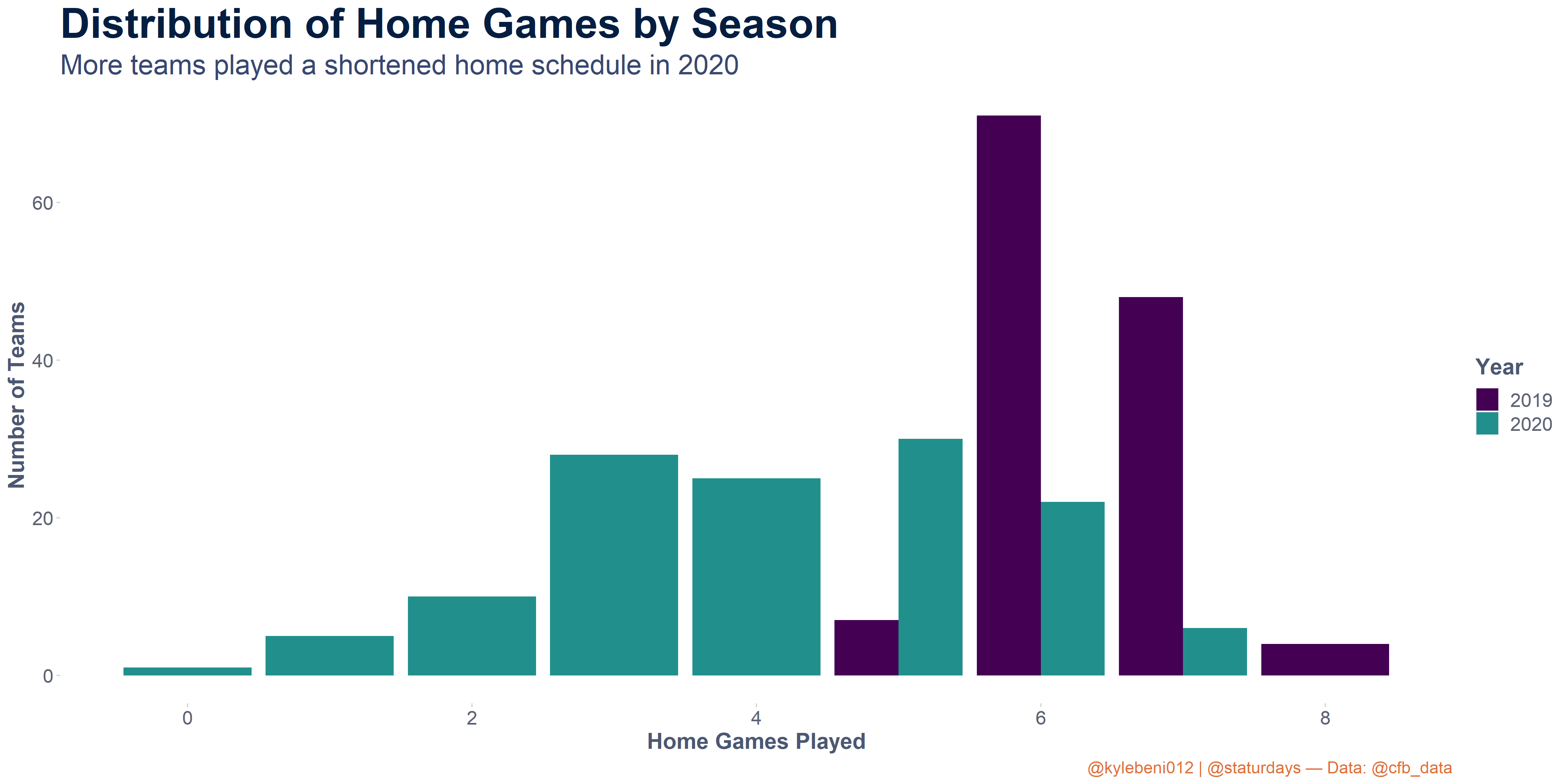

Let’s quickly take a look at how this changed in 2020. We saw previously that there is some relationship between stadium size and home record, but most of that is likely attributable to the people inside that big stadium, not just the stadium itself. In 2020, look at how that advantage disappeared as those intimidating and loud fans became smiling cardboard cutouts.

In almost every season since 2000, the correlation between stadium size and home record was between .2 and .4 and once as high as .41. In 2020, it dropped to historical lows of just 0.08, or almost no relationship between how big a stadium a team was in and how well they played at home. The factor that changed here, of course, was the fans, not the stadiums. And this data includes even the teams that allowed fans for some or all of 2020, so the correlation could have been even worse than this.

So from this plot alone we can see that fans matter a lot more than the stadium size.

So next, let’s try to tease out how much each of these factors matters in the grand scheme of winning football games at home.

Controlling For Team Strength

In order to accurately access the importance of stadium capacity and fan attendance, I need to control for something important: overall team strength. And by control, we really just mean including it as a factor in our regression model. Because without it, the model might confuse stadium size with being more important than it is, simply because it doesn’t know that better teams tend to have bigger stadiums to begin with. By adding in a variable that indicates how good a team is, we can look at similarly-ranked teams and see if their stadium-size has an impact on their performance, given that their overall team strengths are similar.

To do this, I’m choosing to use a team’s away record as a proxy for overall team performance. I could use Elo ratings, or even AP Poll rankings, but I feel like away performances are fair because you have no home-field advantage and it’s just up to your team to perform. This assumes that the quality of away opponents is fairly evenly distributed among teams of different stadium sizes. This may not always be the case, but the majority of the season (3/4 of it) are reserved for in-conference matchups, which are the better games, and non-conference games, if they are easy opponents, are usually reserved for early-season home games (or that week where Alabama takes a week off in November to beat Grambling State by 80).

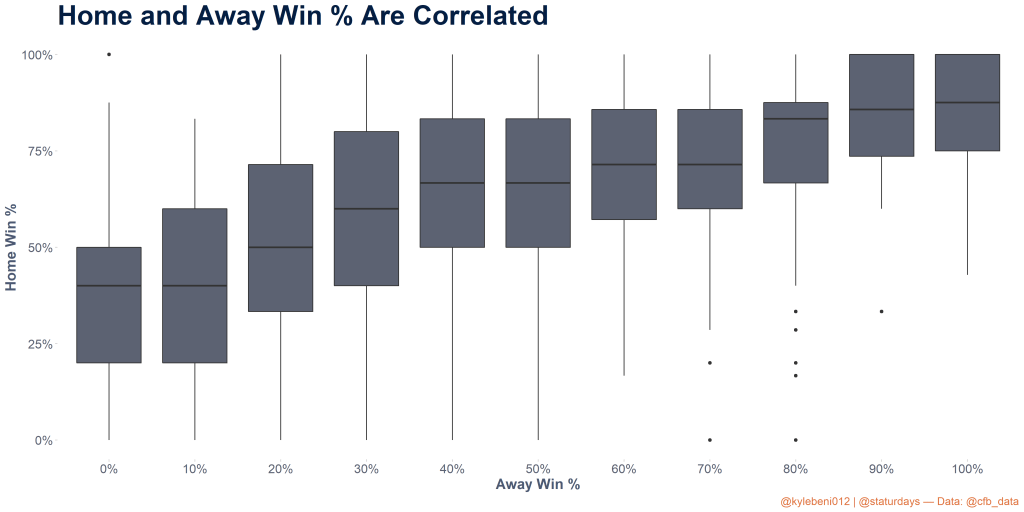

Just to confirm, how teams play at home and away are related, and this relationship is fairly strong.

What Drives Home Game Attendance?

An interesting finding of my data exploration was that home attendance actually correlates more to away performances than home performances. The reasoning behind this might be that fans watch their teams play well on the road, and then get a desire to go see them in person when they’re home. If they watch their team on TV and they stink, they’ll be less motivated to go buy a ticket to see that trainwreck in person.

So teams that play completely average and win 50% of games are better off doing so away from home, as it leads to nearly 15% higher home capacity than doing the same at home.

Building A Regression Model

Okay, let’s finally get into it and put some numbers to these relationships. We’re going to build a linear regression model to see if the relationship between stadium size and home record is significant, along with how significant the other factors like attendance and away record are in determining home record.

Since we’re trying to get an idea of how important each feature is in the regression, we need to ensure that no two variables are too highly correlated. I used Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) to determine this, and found that attendance and stadium size are too similar to use both (they are correlated at 90%), however stadium size and percent of the stadium filled on average are not, so I dropped raw attendance data and instead went with the following three variables:

- Stadium Size

- Average percent of capacity filled

- Away Record

I’m using this to predict a team’s average home record over the course of their games at that stadium. For this reason, I’m using a linear model since the response variable is continuous from 0 to 1. Note: in hindsight, the best model to use in this situation would be a Beta Regression, which is specifically for continuous response variable s between 0 and 1 like my situation, however not knowing much about it, I’m not going to get into it for the sake of simplicity. I’m not doing rocket-science here, after all.

After running the model with those three variables, we find that neither stadium size nor percent of capacity are significant factors when team strength (via away record) is included in the model. This indicates that regardless of the size of stadium a team plays in or how packed the house is on average, they will perform to their best abilities over time. This is fair, but what if we look at an individual game. Can we gain any predictive power by factoring in the crowd size or venue when trying to determine the outcome of one game?

This time, I chose to use logistic regression to see if a model that included the attendance, stadium capacity, and percent of the stadium filled could outperform one that solely relied on the Elo rating of the two teams. We’re using logistic regression because we’re trying to predict a simple True/False of whether the home team won the game or not. This data excluded 2020 because the attendance data is far from complete, so we’ll just assume it’s a normal year. And in a normal year, it turns out that none of those variables are useful relative to Elo ratings alone.

The size of the stadium was the closest variable to being significant, but I would guess that the model was recognizing some of the larger stadiums and starting to correlate that to a better outcome for the home team, when in fact the physical size and capacity of the venue doesn’t mean much. Similarly, the number of people in the stadium or percent of the stadium filled didn’t seem to matter either.