🏁 Checkered Flag

Palou wins the Grand Prix of St. Pete in dominant fashion. He makes it two years in a row winning the season-opener. McLaughlin holds on for 2nd and Lundgaard ends in 3rd, tied with Rinus Veekay for 10 overtakes.

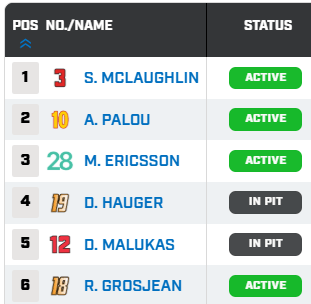

Lap 93/100

McLaughlin and Lundgaard pass Kirkwood!

It’s too late for P1, but the battle for P2 is now Chevy on Chevy.

Lap 92/100

McLaughlin is officially stuck behind Kirkwood, and Lundgaard behind McLaughlin. The gap is under half a second between each of them.

Kirkwood actually has the fastest lap by six tenths with a 62.2, but Palou has been able to maintain a consistently lower lap time overall. He has taken care of the tires and made the fuel go long on the first stint.

Lap 88/100

Palou is actually faster than those on reds behind him now.

Lap 85/100

Still a stalemate on laptime. It’s like Palou knows the pace his competitors are going to run before they run it, and he does nothing more, nothing less. Just maintaining the 5.7s gap.

Lap 82/100

Laptimes among the top 3 stabilized on that last lap. All between 63.2-63.4.

Lap 80/100

The gap is down to 5.5s for Kirkwood. They’re reeling Palou in, but is Palou saving something for them when they get there?

Palou has only made one on-track pass. The rest of the lead was down to his pace on that first stint in-lap, and then his pace on the second stint helped him maintain that lead.

Jameis Winston’s Son

His son has been “studying cars by drawing them.” He’s ready to join an engineering team on the grid.

Kirkwood’s Race

Kirkwood has moved up 11 spots with 9 overtakes.

Push to Pass

Palou leads the top 3 with 90 seconds of PTP. McLaughlin with 80, Kirkwood with 51.

Lap 74/100

McLaughlin and Kirkwood are pushing about .5s per lap faster than Palou.

Lap 73/100

Effective order:

- Palou

- Kirkwood (-7.2)

- McLaughlin (-8.6)

Lap 69/100

McLaughlin in.

Looks like teams are prioritizing safety against a yellow to a short final stint. Seems the tires are holding up on the longer stints.

Lap 67/100

Palou is in. He’s looking at a 32 lap black stint. I’m a bit surprised he didn’t take the reds longer.

Lap 66/100

Armstrong made a wild attempt into Turn 1 and gave up 2 spots in the end. The field is getting racy.

Now Lundgaard gets by as Ericsson dives into the pits.

Lap 65/100

McLaughlin moves into P2 with an overtake of Ericsson into Turn 1.

We’ll see what kind of pace he has with clear air as he chases down Palou.

Lap 59/100

To add to the pain, Palou’s pulled out a 6 second gap on P2.

Fuel Update

Palou has 3 laps on McLaughlin and 2 laps on Ericsson. He’ll be able to go deepest in this stint. Quickest final stop should be in store for him.

McLaughlin’s best hope at this point could be to pit on the early side and hope Palou gets caught out with a yellow. You’re not going to win the fuel-save battle against him at this point.

Lap 55/100

Last lap times:

- Palou: 63.0

- Ericsson: 63.9

- McLaughlin: 64.0

All on soft reds.

McLaughlin’s First Stop

Traffic and slow in laps hurt McLaughlin. He didn’t pull away from Ericsson or Palou on his in laps, and then got stuck battling on his out laps.

🟩Green Flag – Lap 44/100

Palou leads. He will need to take hard black tires for the final stint (presumably around lap 80). McLaughlin will have the tire advantage on a set of soft reds.

🟨Yellow Flag #2

McLaughlin Radio

Their goal is track position and going “at least as long or longer” than their competitors on this stint.

Effective Order

Palou, Rossi, Ericsson, McLaughlin, Armstrong

Radio

McLaughlin’s engineer is saying “Woulda coulda shoulda” on how deep they took that first stint.

Dixon lost his right rear. Loose wheelnut. So unfortunate.

Stint 2

Lap 40/100

Pit sequence complete and the overcut was the clear winner.

Lap 38/100

Palou just did a 62.8. That was a much faster in lap than McLaughlin was a ble to do on the hard tire.

Editor’s Note

The live map is about 20-30 seconds ahead of live radio, which is about 2 minutes ahead of the broadcast. Makes it pretty hard to keep track of what’s happening when.

Lap 36/100

McLaughlin in.

Lap 34/100

McLaughlin is pushing, a 63.9 on that last lap. Now a 63.5. The soft runners behind are mostly keeping up though.

Lap 32/100

Rahal in 9th up 5. Dixon up to 11th with 6 overtakes and 2 pitstops in hand. Watch out for him. He’ll be able to take this stint longer, get on cycle with the others, and have a shorter final pitstop because he’ll need less fuel.

Lap 27/100

I spoke too soon. There’s no discernable difference between softs and hards from what I can see in the recent laptimes.

Lap 25/100

Will Power is out. Same spot as his previous incident.

Radio: “12 more laps on these tires”. Looks like the target lap is 37.

Reds appear to be falling off now, about .2-.5 slower than the blacks.

Lap 23/100

O’Ward is the fastest on the primaries of those yet to pit, with a 63.7 last lap.

Lap 21/100

Radio: “Tires starting to go” according to Louis Foster.

However, the primary hard tires were slower last lap. The leaders did a 64.1 and the first soft runners did a 63.8.

Lap 19/100

This is looking to be a 2 stop race. Same start, different result. Perhaps due to the two-soft rule.

Radio: Half tank of fuel was the call. Could put the absolute last stops around lap 37/38.

Lap 17/100

The hard and soft tires are both equal still at this point in terms of lap time, it appears. Both tires running around a 63.4.

Lap 16/100

Alexander Rossi has 1 pitstop done and 5 overtakes complete. He’s in P16 at the moment.

Lap 13/100

Anddddd Malukas’s left front gave out. He’s nursing it back to the pits.

Lap 7/100

Malukas has flatspotted his hard tires already. He’ll have to get them through the next 7 laps at least before he thinks about going to softs, but imagine he’ll be an early pitter once the window opens.

We’re green again.

Yellow Flag

One notable early pitter: Scott Dixon.

So far no takers from the lead group on pit row.

Radio: lap 15 is the target lap for the first stint to optimize the stint length on the red tires. Per the broadcast, teams will need to do two stints on reds.

Stint 1

Look for early pitstops similar to last year.

Full course yellow already after there’s commotion in the back: Schumacher, Ferrucci, Sting Ray Robb involved.

Green Flag

We’re green!

Command

There’s the command. We’re moments from the green flag.

Strategy

Last year, the first 6 laps were under caution and then the race went green the rest of the way.

The winning strategy from Palou was a lap 2 stop, and then two more stops on laps 39 and 72, for 3 stops total.

The early last stop allowed Palou to take over the lead on lap 75 and never look back.

Look out for:

- Taking cheap stops under yellow

- Pitting early rather than going long

Grid Walk

I can’t believe I’m saying this but Jameis Winston actually crushed that grid walk assist. He’s a natural.

Pre-Race

Betting Odds

If you’re a betting person, the odds for race one are intriguing. Palou (4th) is favored at +170 to win. McLaughlin (1st) is at +230, Ericsson (2nd) is at +900, and Hauger (R)(3rd) is at +1800.

Track Stats

To recap from yesterday:

- the pole winner wins this race 19% of the time.

- The top 5 win this race 71% of the time.

- Someone in the top 10 wins this race 90% of the time.

So we’re looking at any of McLaughlin, Ericsson, Hauger, Palou, or Malukas with the best shot to win this race. McLaughlin, Ericsson, and Palou have all won here before.

O’Ward (8th) is the only other driver in the top 10 to have won here before.

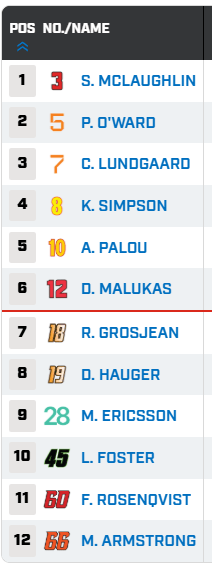

Starting Grid

We’re about 15 minutes away from the start of the first Indycar race of the 2026 season. Scott McLaughlin starts on the poll, with Marcus Ericsson 2nd and rookie Dennis Hauger 3rd. Palou is starting 4th.

Here’s the full starting grid.