If you work in python package development or maintenance, then your world may have stopped for a few hours on Monday afternoon.

To most, it probably felt like one of those “random” errors that pops up one day and is gone the next, but behind the scenes were hundreds of developers arguing back and forth on the public GitHub repository of setuptools over the best way to rectify a breaking change that broke more than anticipated.

What Happened?

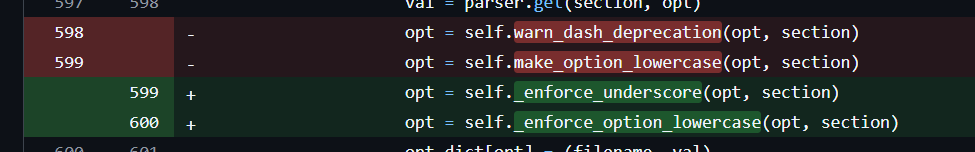

It all started on Monday morning with a major release of setuptools which began failing build for what was previously a deprecation warning about using dashes or uppercase characters in your setup.cfg file.

Previously, setuptools would quietly fix your file for you, but for some reason in v78 they decided to start enforcing it.

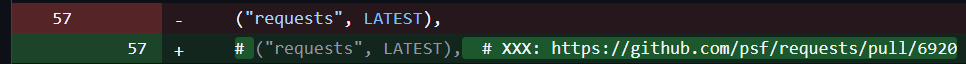

Funny enough, the 78.0.0 release initially failed because their own tests were failing due to a dependency, requests, not complying with their new rule. Rather than viewing this as a sign to take a moment to pause and consider the potential impact, they decided to comment out the tests.

I say “they”, but in reality this was the rash decision by one individual developer who opened and merged their own PR with no reviewers, no requests for reviewers, and no comments.

Once this release made it onto PyPI is when the trouble for everyone else started.

It seems innocent enough: starting with v78, you need to correct your naming. It’s a simple fix. The problem was twofold, though:

- If you didn’t pin a top version of setuptools in your build specification, the newest version started being used by default, potentially breaking your package.

- Even if you fixed your own package, if any of your dependency packages were out of compliance (and not pinning their version of setuptools), then they would also cause your build to fail, namely if their package needed to be built from source (as is the case in Linux). This is why the pain was most immediately felt in a lot of people’s CI workflows on GitHub.

So now there was this cascading effect of having to fix your own package (no big deal, usually), but then having to ask others to fix their packages (many of which–as many in the comments of the faulty PR pointed out–were no longer being actively maintained).

Again, all of this was apparent when the setuptools tests themselves were failing because of requests (a python software foundation package) being out of compliance.

How Was It Resolved?

Fairly quickly, issues started popping up in the repos of packages that were out of compliance asking them to quickly fix their setup.cfg files. It’s hard to say how many packages were out of compliance, but rest-assured it would’ve taken weeks to months to get everything resolved across all the packages out there. People quickly realized this was too big an issue to deal with in this way. In the case of one package, pyspark, the fix was opened in a PR, but the pyspark tests take several hours to run (and they failed), so it was not exactly a quick-fix and they needed to do that on several still-supported minor versions of the package.

So, the discourse in the setuptools PR space was to revert the changes and yank the bad versions in the meantime. Thankfully this only took a matter of hours, the release succeeded, and things quickly went back to normal. However, it revealed a lot of the flaws in open-source software development and the inherent risks of relying on these tools that we take for granted on a daily basis.

What Did We Learn?

1. Pin a Version Range

If every package had set a max version of setuptools to something they knew they were compatible with, then this wouldn’t have happened. Of course, we can only control what we do in our own package. In this case, pinning setuptools wouldn’t have helped us if our dependencies didn’t do the same, but generally this is not the case and pinning our requirements can save us from running into these breaking changes unexpectedly. For GitHub Actions, pin a specific, immutable commit hash.

2. Don’t Ignore Deprecation Warnings

While I still think this breaking change was done poorly, the fact is that this deprecation warning was out there since 2021. When you ignore deprecation warnings, you’re taking a risk. Unless you are completely pinned down.

3. Choose Your Dependencies Wisely

When designing your system, build around well-supported and actively maintained projects. Leveraging fringe packages with little support or below their first major version release is risky, especially at the enterprise level where reliability matters.

4. Respect SemVer

For all the criticism, one thing you can’t argue is that setuptools followed SemVer. Most people cannot say the same. If you are instituting a breaking change, you must increment the major version number. This indicates to your users that it is not necessarily safe to just bump the version without checking things out first. You can tell that most people do not respect SemVer because most packages, even long-standing ones like numpy and pandas, are still only on version 1 or 2. The odds that they have not incorporated at least some if not many breaking changes in all those patch and minor versions is low.

5. Understand Why Your Tests Broke

Writing tests can be hard. Understanding tests is even harder. Debugging odd failures, especially ones that pop up during CI/CD, can feel insurmountable. However, it’s an essential skill and, as we saw on Monday, can be the difference between catching a crucial issue and unleashing hurt on others. Had the setuptools developers actually resolved the cause of their test failure rather than commenting it out, they would’ve seen that the solve was going to cascade to hundreds of other packages and maybe would have held off on the release until they could effectively communicate the change with others.

6. Don’t Merge Your Own PR’s

This might be the golden rule in my opinion; it really is that important. You cannot just shoot from the hip, especially on a public repository that is such critical infrastructure to the python packaging community. Request reviewers. Get a second and third pair of eyes on your code. Had they done so, someone certainly would’ve questioned why commenting out a test was the best course of action.

7. Deprecation Warnings Need to Come With A Timeline

Crazily enough, a user in the discussion tab of the setuptools repo predicted this exact situation almost 3 years ago. They asked how they were supposed to determine which deprecation warnings were most urgent, noting that the one in question about naming syntax of config keys seemed “minor”.

If you are planning to deprecate something, saying “will be deprecated in a future version” isn’t specific enough. You need to set a specific version or a specific date by which action needs to be taken.

Additionally, you need to weigh the benefits and drawbacks of implementing these deprecations. When I told my coworker about the issue and the scope of people affected, his response was “all this over a stylistic choice?” Some things are not worth the trouble of enforcing if there’s no security, performance, or functional benefit to implementing it.

Packages can throw out so many warnings that you become numb to them, so you really need to pick and choose your battles as a package developer.

And the next time someone brings up the potential for something to maybe break a year or two from now, don’t roll your eyes! We just saw it happen, and it is destined to happen again soon.

Is Open Source Actually The Holy Grail of Security?

I’ll finish with a final thought: I tried to explain this situation to my fiancé Raychel: how one random guy in the UK brought down our and so many other packages around the world. She couldn’t believe that my company was relying on the packages of so many others outside of our control, and the contributions of random people around the world that we’ve never met. “That doesn’t sound very secure,” parroting back a phrase I often say to her in relation to her job.

“No. Open source is the most secure because everyone can see it.” I told her this because it’s what I’ve been told. But between the setuptools issue that morning and the tj-actions security incident the week before, I was questioning this premise.

Sure, the issues can get rectified fairly quickly once they’re noticed, but usually the damage is already done. The data was stolen, secrets exposed, or time lost. If one random guy in the UK could shut down packaging work for an afternoon, what else was possible? I think open source is for sure still better than the alternative, but it has its flaws, and some tightened guidelines around these critical packages–such as requiring PR reviewers–would be a really simple step in the right direction.