Now before you close out of this article, I’m going to warn you: I’m going to bash college football, the sport you and I both love, a lot during this article. I’m also going to give it some credit. Please don’t get mad: I’ve tried to give as fair and thorough an analysis of the college football season as I can. So if you’ll stay with me through to the end, hopefully you’ll agree.

The 2020 college football season comes to a close with Alabama crowned champion in a season like no other before it and hopefully after it. However, there’s an empty feeling inside as I reflect back on the season we just witnessed. Sure, there were some highs, some great moments, some exciting games enjoyed by fans and casual viewers alike. But it left me with a hollow feeling, as empty as many of the stadiums where the games were played this year.

So I wonder: was playing college football in the fall of 2020 worth it? Was it the right decision? Was the benefit of a partially funded athletic department worth the unknowable number of additional COVID cases and deaths sourced from outbreaks at practice facilities around the country? Let’s go through the pros and cons of a season made up of perseverance, protocols, and conflicting priorities.

One more quick note: you’ll notice a lot of the pros have cons mixed in, and a lot of the cons have pros. This was inevitable as I wrote and found multiple sides to each story, and further illustrates the gray area we are all living in each day amid this pandemic. There is no single right or wrong answer to most things.

Why the 2020 season was a success

We got through it. And I don’t mean got through it like the NFL is boasting getting through 17 weeks of football in 17 weeks. We got through it by playing when we could, and cancelling when we had to. Yes, there were cancellations, but rightfully so. It is a good thing that we cancelled games when there was an outbreak, and didn’t try to play through it. That should be celebrated.

Kids got exposure for the NFL. This is a benefit that only affects a select few, but undoubtedly, there were new stars made this year that may have missed their shot if they graduated without playing their last season.

It probably didn’t make much a difference in the grand scheme of the pandemic. It’s hard to point the finger at college football and say they did anything egregiously worse than the rest of the country. We’re all just trying to get by. If everyone else was quarantining and college football was trudging on, then that would be a different story. Dr. Doug Aukerman, senior associate athletic director for sports medicine at Oregon State, argued that college athletes were incentivized to be good followers of COVID safety protocols by being able to play their sport as the reward. I don’t disagree with that logic, and fans and other students may have bought into mask wearing when they saw Nick Saban, Trevor Lawrence, or their local campus stars wearing theirs around campus and in-press conferences on national television. They were probably also negatively influenced by seeing Dabo Swinney and many other coaches pull their masks down every time they had something to say, or perhaps it was just amusing.

Fans stayed home on Saturdays and watched college football. Depending on who you ask, ratings are up or down this season compared to 2019, but likely down due to cancellations and teams not playing, or playing shortened schedules. For the National Championship, the ratings were the lowest since 2004. Despite the ratings, there was a group of fans that chose to stay home and watch college football on Saturday, who may have otherwise tried to go out and find something to do to cure the boredom.

Now, a few caveats. Watch parties would be counterintuitive to my whole point, and those surely occurred, but hopefully at a much lower rate, or distanced and outdoors. There were, of course, fans in-person at many games as well. Sporting events mean crowds, shouting, and strangers: two of which the CDC lists as risk-factors. Shouting has also been labeled as an unsafe behavior. The one benefit is that games are held outdoors.

In addition, we’ve seen plenty of chin-mask or maskless fans on TV, the mass celebrations that occurred after Alabama won the National Championship this week, and Notre Dame students rushing the field after upsetting Clemson. To Notre Dame’s credit, every student appeared to be wearing a mask, and my quick review of Notre Dame’s COVID cases didn’t show any notable spike in the weeks after that game. The same can’t be said for Alabama fans, many of whom were maskless since they weren’t in a controlled environment like the Notre Dame fans were.

Finally, there are other ways to keep people entertained on the weekends that don’t rely on compromising the wellbeing of 18-22 year old amateur athletes. The NFL could have easily taken over Saturdays and spread their games across the entire weekend slate. That would have probably drawn more viewership than college football could, while still keeping the masses entertained all weekend without it being at the expense of unpaid student-athletes.

It funded athletic departments and kept thousands across the country employed. Whether it meant employees of the university continuing to get paychecks, or local businesses seeing a little business in town with a small crowd, as opposed to no business whatsoever: college football propped up economies across the nation. Smaller, revenue-losing sports were kept alive in some cases. Not to mention the networks and their employees who had content on Saturdays, articles to write, shows to produce, and ad space to sell.

Why the 2020 season wasn’t worth it

A lot of players got COVID, and we don’t know what that means for them in the future. Not six months from now, or six years from now. We have seen studies showing increased risk of heart conditions, brain fog and other ailments lasting many months after infection, and more.

Athletes (generally, based on my analysis of the Big Ten) got COVID at a higher rate than their peers, meaning that it was not indeed safer to play sports than to not play, as many argued. And how could it be? Would you feel safer in a spread out classroom (or much more likely, in your dorm on Zoom) with a mask on, or huddled up in the locker room celebrating post-game? Many schools implemented regular random testing, returning positive rates of around 1% at schools like Penn State, Alabama, and Clemson. Even during the worst parts of the pandemic (read: now), the positive rate is around 15% nationwide.

However, we’ve seen how quickly COVID spreads in a locker room. Ed Orgeron notoriously said “most our players have caught it”, without citing any data. The Clemson locker room had an outbreak almost immediately when they got back on campus, with 23 players infected. On a roster of about 100 players in CFB, that’s a 23% positive rate. This is clearly higher than the rate of spread that casual students on campus were experiencing (the Clemson positive rate currently, even during the new height of the pandemic, is only 2.5%). Athletic departments in the Big Ten with complete datasets averaged around 8% of all cases at their respective universities, ranging from 2% of all cases to 21%, much more representative than their makeup of the overall student-body in most cases, with most Big Ten schools having somewhere between 40,000 and 60,000 students.

They also probably gave it to their peers, where it slowly leaked out and decimated vulnerable residents in college towns. It’s impossible to know how many other people these players potentially infected. Nobody is writing headlines about the roommate of the college football player who is in the ICU, or mother or Aunt or professor. It’s a rolling ball that just keeps growing.

While infection rates, hospitalizations, and deaths among university students were low compared to the general population, the same can’t be said for those living in the surrounding areas who were at higher risk. All it took was a few interactions between student and townie to send the virus through a college town.

Players and teams that wanted to play, didn’t feel that way so much by the end. As seen by the bowl game opt-outs (at least 21 teams formally opted-out, forcing 16 bowl games to be cancelled), and a post-mortem done by Sports Illustrated, the enthusiasm was high at the start of the season, and quickly dwindled, a feeling we can all probably relate to. That being said, at least one player interviewed said it was 100% worth it despite their disinterest in competing beyond the regular season.

Kids were forced to make extraordinary sacrifices. Not seeing family or friends for months at a time. Being deemed “essential” employees as student-athletes. People will argue it helped their chances at the NFL. Most will not play in the NFL. People will say they were given the chance to opt-out without consequence. When there is uncertainty, and no guarantees from the NCAA, that your scholarship will be waiting for you next year instead of handed to an incoming freshmen, is that really without consequence? Coaches were also caught telling kids to hide symptoms, as detailed in a report with mixed conclusions and no consequences.

Coaches, ADs, even parents, also actively lobbied their conferences to return to play because their kids wanted to play. A lot of people also want to dine indoors, open up bars, or beat COVID via herd immunity. However, kids (and many adults, as we all now know), don’t always know what’s best for themselves, or others around them. So listing “the kids want to play” as a reason to play is irrelevant during a pandemic. People want to do a lot of things they shouldn’t do.

Coaches COVID-shamed other programs. Most notably, Dabo Swinney claiming Florida State blamed COVID to get out of a matchup between the two teams. This type of squabbling, as thousands died each day, belittled the seriousness of the pandemic.

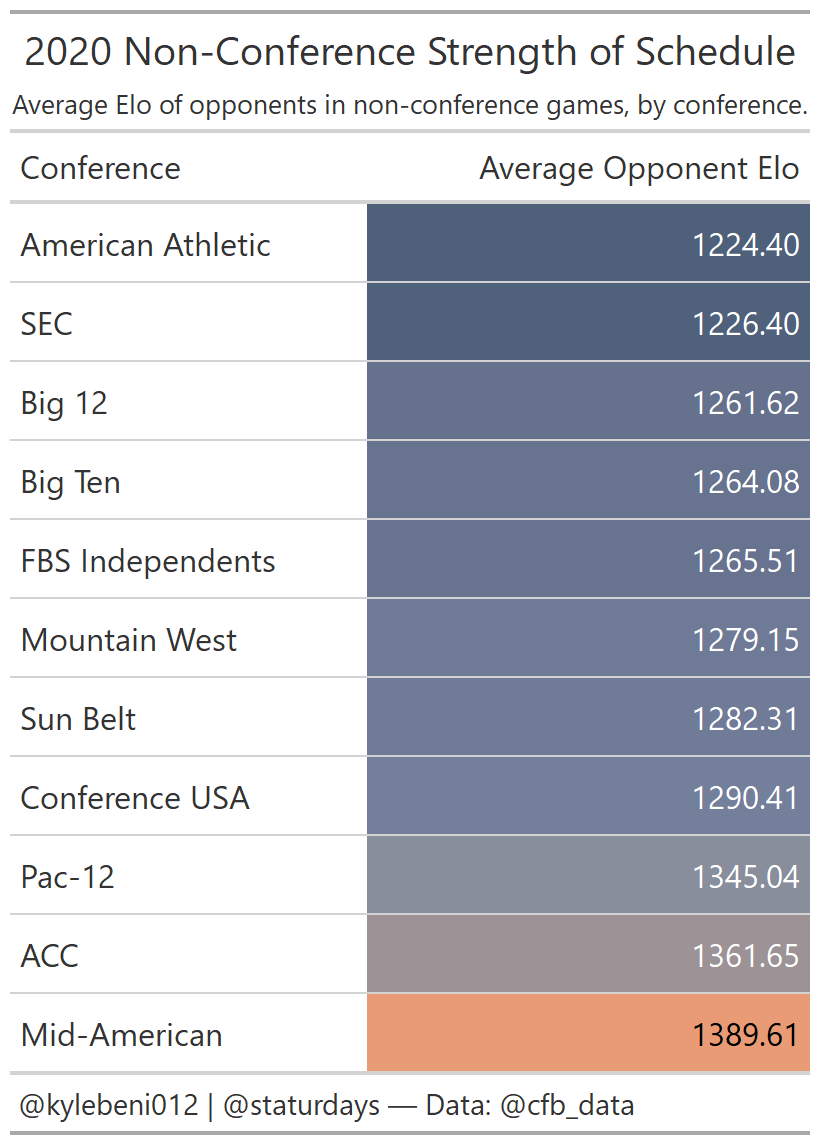

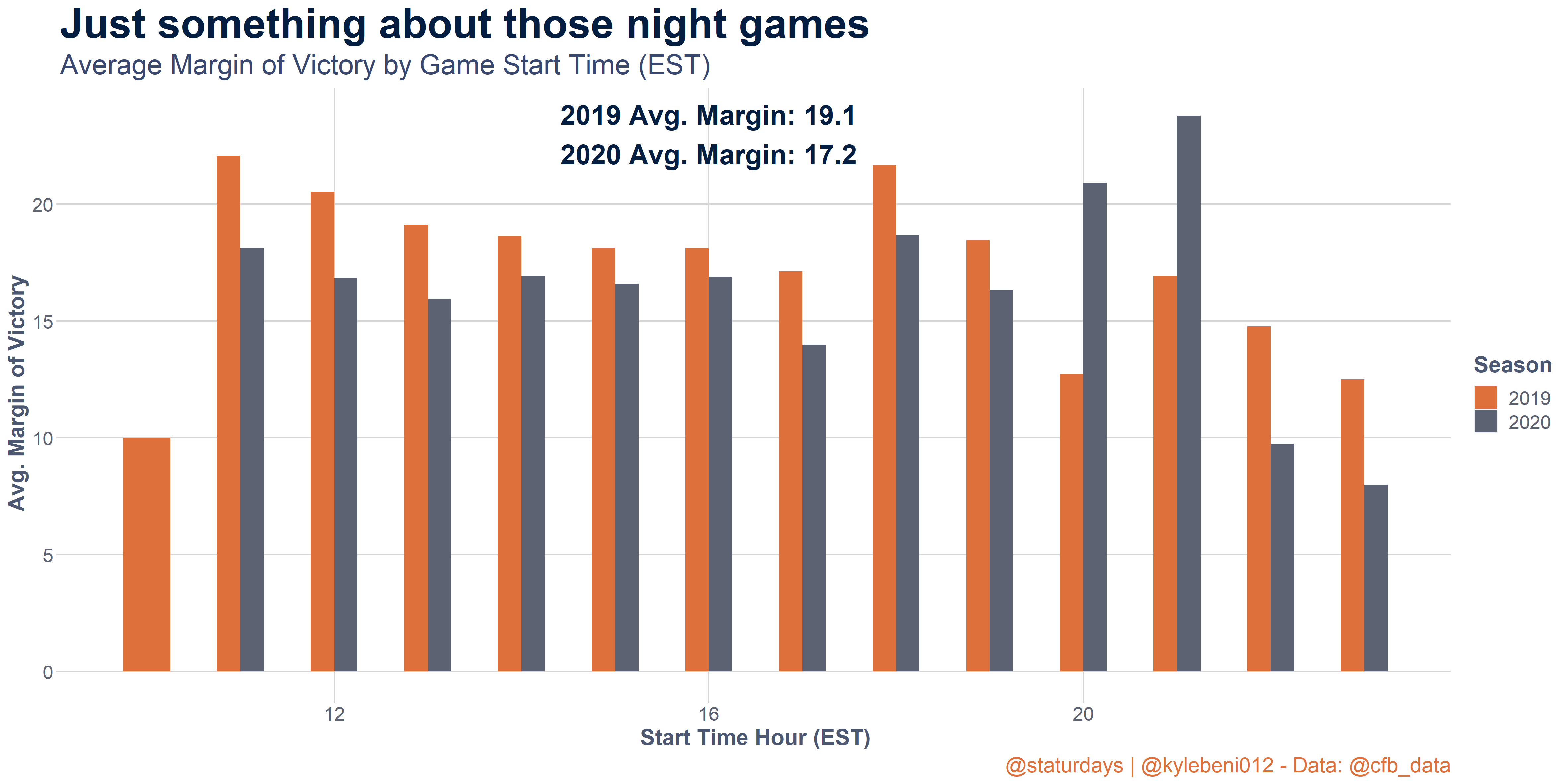

There were a lot of prime-time blowouts. It certainly felt that way, at least. But was it an unbalanced season? The actual margin of victory in 2020 was nearly 2 points less, at 17.2, than it was in 2019 at 19.1. But that could be due to the elimination of most blowout non-conference games. So when excluding non-conference games, 2020 still had a 0.5 point advantage over 2019 at 16.1 points. However, when you look at the start time of games, the 8-9 PM Eastern Time games (primetime) in 2020 had the largest margin of victory at 23.8 points. So we can agree that the primetime games sucked this year, but let’s not say the whole season was that way.

The scheduling differences made the race to the Playoff more unfair than normal. A 7-0 team played a 12-0 team in the National Championship. I’m not saying they didn’t deserve to, but a lot of people didn’t like seeing that, and I don’t blame them. A lot of good teams got left out, which is an issue that goes beyond just 2020. And viewers made their opinions heard by not watching, whether because they didn’t like the teams, or thought it was going to be yet another primetime blowout.

We lost a college football player to COVID-19. I wrote at the beginning of the season that if we lost even one player to COVID-19, it would not be worth it. Now, from what they know, it sounds like the infection was linked to a party, and not a football activity, so I don’t think it would be fair to attribute this to college football in any way. His team was not playing in the Fall, and students were going to return to campuses whether football was played or not. Still, this is of course very sad to hear.

Jamain Stephens Jr., a defensive lineman for California University of Pennsylvania, died from a blood clot in his heart after contracting Covid-19. “I’m very, very nervous for these young men and women … These kids, their lives are priceless. And it’s just not worth it,” his mother, Kelly Allen, told CBS News.

This excludes high school football, which I would argue was many times more dangerous given the number of high schools there are for each individual D-I program out there. Several high school coaches have lost their lives from the virus. And high schools don’t have the resources to test their athletes like these colleges do: without rapid and regular testing, college football likely wouldn’t have been feasible.

So was it worth it?

I feel guilty, like my enjoyment of the season came at the expense of young athletes’ wellbeing, and potentially people’s lives. It’s the same way I feel when I eat out at a restaurant and shamefully remove my mask while a minimum-wage server takes a deep breath and comes to wait on me, praying I won’t be rude or ill. “I’m supporting local business. She’s glad that I’m here. It’s better than the place being empty.” But my dollar is just as good picking up takeout without putting her or other diners at risk, so why am I here? It’s the guilt we battle with every day.

I stand by my statement at the beginning of the season: if we lost even one player, coach, or assistant from COVID that could have been avoided by not playing football, then it was not worth it. Luckily, as far as we know, no college football program lost someone due to COVID-19, despite the large number of infections. I cannot definitively say that for all college sports, but that’s something to be thankful for.

The waters have been muddied so much by the irresponsibility of the nation as a whole that it’s impossible to point the finger at college football and say “this is your fault.” With that being said, we’re all just doing the best we can to get by. And college football helped a lot of people—not just players, but staff, employees, cameramen, analysts, fans, and myself included—get through a very rough part of 2020.

A lot of bad has come from this year. A lot of bad has come from college football. But in a year where we’re all searching for what little bit of good we can find each day, college football delivered some of that too.