You’ve heard of home-field advantage, but it’s always in the context of the advantage that a home-crowd gives a team. But what if that stadium were empty? Well sure enough, we saw just that last year.

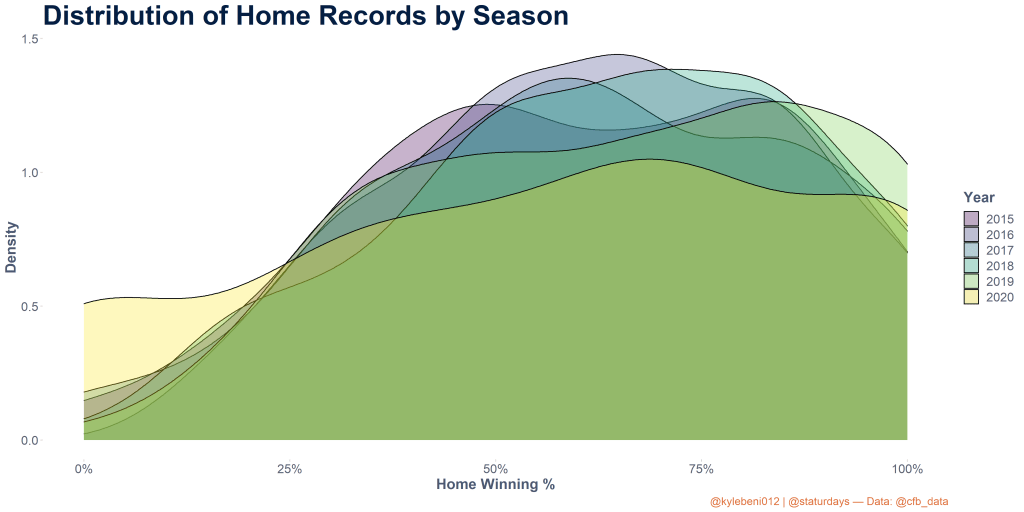

Home-field advantage changed in 2020. That’s for sure. But by how much and why is less certain. Take, for instance, the distribution of home records over the past 6 seasons. As you’ll see, 2020 saw more teams with weaker home records, some getting shut out completely, a rare occurrence in past years.

However, this doesn’t tell the full story, because, as we know, in 2020 teams played abbreviated schedules and dealt with last-minute cancellations, leading to a smaller slate of home games for some teams. Here’s the distribution of the number of home games played in 2020 vs. 2019.

So more than half of D-I teams played 4 or less home games. This led to a lot of variability in their results. Almost every conference also played an exclusively conference-only schedule last year, upping the quality of their competition in those home games. Naturally, we’d expect their home-record to drop as the average quality of their opponent went up.

When we filter for only those teams that played at least six home games in 2020, we get a much different story.

Well now what? This looks like teams actually played better at home when they got their 6+ games in. And in fact, they did play better on average at home in 2020 than the overall average in the previous five seasons. Teams in 2020 won 71% of their home games when they played six or more of them. From 2015-2019, that number was 64%. The difference is statistically significant with 95% confidence.

That being said, when you include all teams, regardless of how many home games they played, the difference between home-records in 2020 was statistically significantly worse than the preceding five seasons. So when teams were able to get all their games in, they saw improved home-field advantage, and when they didn’t get their normal games in, they struggled at home.

So how can we make sense of this trend? I don’t know that we can entirely understand the difference. Only 28 teams out of 127 got 6 or more games in in 2020. 10 were from the ACC, and then a mix of Sun Belt, Independent, Conference USA, and a few Big 12 and American Athletic conferences. The overwhelming majority of these teams were from the South, where eased restrictions meant more fans at home games, which could have given them improved home-field advantage.

Elo Ratings between the two groups were almost identical going into 2020, but were 50 points higher when the season ended for the teams that played all their home games.

We also need to remember that conferences like the Big Ten only played 9 games, all in-conference. So we would expect their win percentage to decrease significantly in a season where they effectively lost one or two near-guaranteed home-wins against non-conference cupcakes. Who knows what would have happened with an extra three games. We saw teams start off slow and finish the season on a run, adjusting to the new normal of the 2020 season. We also saw teams fall off, falling victim to opt-outs, infections, and lack of motivation.

So while, in part, the full-season teams played better than usual, it is likely that had more teams gotten in a full-season’s worth of games, they would have dragged the home-field advantage down to below-average levels. There is no doubt that the overall landscape in college football favored the away team more than in any other season in at least the past 20 years.

This year, we’ll see how much that home-field winning percentage rebounds as fans return in full force in most stadiums. And we can’t wait to see it.

Have a theory about why those 28 teams played better at home in 2020? Email me at kyle@staturdays.com or tweet us @Staturdays on Twitter.